Administrative work in universities is full of documents that must look serious and official. Strategic plans, accreditation reports, assessment summaries, memos, program reviews. These texts are often written in a careful, dry tone that tries to sound objective and important. For me those documents felt like a toll road that I had to pay to get to the interesting parts of the job. I wanted to talk with faculty, students, and community partners about real issues. I wanted to design new programs and rethink old ones. Instead I spent hours polishing language that almost nobody planned to read.

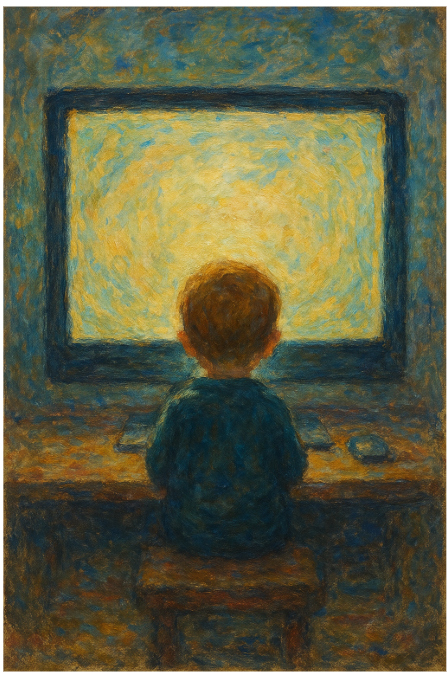

When large language models became usable, something in me clicked. Within days I was intellectually convinced that this technology would matter for education. But I also had a powerful emotional reaction. This felt like a long delayed form of liberation. A big piece of my working life that had always felt wasted could now be reclaimed for thinking and for human interaction.

I do not experience AI as a threat to meaning or to craftsmanship. I experience it as an assistant that removes the crust from the work. I still need to decide what the document should say, who it is for, what matters and what does not. But I do not need to fight with first drafts, with standard phrases, or with the sheer volume of institutional writing. AI gives me more time for the activities I actually value: creative thinking, brainstorming, problem solving, building theory, and talking with real people.

This personal relief also made me more cautious about judging other people's reactions. Our field often talks about AI as if there is a single rational stance to take. In reality, psychotypes matter. Some people are wired to enjoy the very things that I dislike. They take pleasure in the slow craft of sentence building. They value the aesthetics of a beautiful paragraph, the elegance of a careful transition, the feeling of a page that has no awkward phrase anywhere. The process itself is rewarding for them, not just the outcome. These are not shallow preferences. They reflect different theories of what work should feel like and what makes it meaningful.

There are also people for whom accuracy and authority are core values. They want information to be correct, checked, and stable. They trust texts that feel final. For them, any minor error, even a typo, can cast doubt on the whole product. When they look at AI, they see a tool that produces fluent but sometimes wrong text, and that feels deeply unsafe. The idea that something could sound confident and still be mistaken violates their sense of how knowledge should be handled. Their resistance grows from a coherent set of commitments about what scholarship requires.

My preferences run in a different direction. I care more about speed, access, and the flow of ideas than about perfect reliability at the sentence level. I was an early fan of Wikipedia for exactly this reason. I liked the fact that I could reach a reasonable overview of almost any topic in seconds, even if I knew that some entries had gaps or errors. Many colleagues still treat Wikipedia as second rate. For me, being mostly correct is good enough, as long as I can see interesting ideas and follow references further if needed. This is a different epistemology, not a careless one.

AI feels like an extension of that tradeoff. It gives me fast, flexible text that I can shape, question, and rebuild. I do not expect it to be right in every detail. I expect it to help me think faster and wider. What I cannot easily get without AI is a steady partner that never gets tired of drafting, revising, or trying a different structure for the tenth time. The machine does not care how many times I change my mind. That patience has real value.

In one of my earlier reflections I argued that doing a task very well does not prove that the task itself is worthwhile. AI has pushed that point closer to home. Many academic and administrative texts are produced with great skill, but the value of that effort is not always clear. If a machine can now produce a comparable draft in seconds, it becomes easier to ask what exactly we are adding with our human labor, and whether we want to spend our limited time there. This is an uncomfortable question for professions that have built identity around textual competence.

The issue goes beyond individual preference. Different psychotypes produce different institutional cultures. Organizations dominated by people who value routine and formal documentation will resist AI more strongly than organizations where improvisation and speed are prized. These cultural differences shape what counts as quality, what gets rewarded, and who advances. When AI enters the picture, it does not just change tools. It shifts the balance of power between competing visions of professional life.

When we think about AI in education, we should factor in these differences in temperament. Policy debates tend to focus on abstract risks and benefits. Underneath those arguments lie different ways of relating to work, to text, and to uncertainty. People who experience AI as freedom will advocate for rapid adoption and experimentation. People who experience it as erosion of craft or trust will ask for limits and safeguards. Both groups have a piece of the truth. The challenge is to build systems flexible enough to accommodate both without forcing everyone into the same mold.

Any serious conversation about AI in education has to make space for multiple stories and for the many shades in between. What we cannot afford is to pretend that these differences are merely technical, or that one good argument will settle the matter for everyone. The stakes are partly emotional, partly philosophical, and deeply tied to how we understand the purpose of our work.